Note on Power of the Police to Arrest by Legum

Power of the Police to Arrest

Introduction:

This note will discuss the power of the police to arrest with or without warrant.

Meaning of an Arrest:

According to the Black’s Law Dictionary, 9 th ed., an arrest is:

1. A seizure or forcible restraint.

2. The taking or keeping of a person in custody by legal authority, esp. in response to a criminal charge; specif., the apprehension of someone for the purpose of securing the administration of the law, esp. of bringing that person before a court.

In the case of Amadjei and Others v. Opoku Ware (1963) 1 GLR 150 , the court characterised an arrest as follows:

Arrest does not mean simply that a person is taken by the police to a police station. There is an arrest whenever there is a restraint of liberty, with or without actual confinement. There is an arrest when a police officer makes it clear to someone that he cannot go out of the presence and control of that officer, and when a suspected person makes a real submission to a request or command by a police officer.

Mode of Arrest:

Section 3 of the Criminal and Other Offences (Procedure) Act, 1960 (Act 30) , provides that:

In making an arrest a police officer or any other person making the arrest, shall actually touch or confine the body of the person to be arrested, unless there is a submission to the custody verbally or by conduct.

Thus, if the person to be arrested submits to custody, either by his words or by conduct, there is no need for the police to touch or confine him. However, if he fails to submit to custody, the police can touch or confine him.

What the Police Must or Can Do After Arresting a Person:

First, the police is mandated to inform the person arrested of the reason for the arrest. This is provided in Article 14(2) of the 1992 Constitution , which reads:

A person who is arrested, restricted or detained shall be informed immediately, in a language that he understands, of the reasons for his arrest, restriction or detention and of his right to a lawyer of his choice.

Second, the person must be brought to the court within 48 hours after his arrest. This is provided in Article 14(3) of the 1992 Constitution . Also, see the case of Kpebu v. Attorney General [2019] GHASC 90 (18 December 2019) .

Third, the police can only subject the arrested person to restraint that is necessary to prevent his escape. This is provided for Section 6 of Act 30, which reads:

A person arrested shall not be subjected to more restraint than is necessary to prevent the escape of the person arrested.

Third, the police have the power to search the arrested person. This is provided for in Section 8(1) of Act 30 which reads:

When a person is arrested by a police officer or any other person, the police officer making the arrest or to whom the other person, makes over the person arrested, may search the person arrested, and place in safe custody the articles, other than necessary wearing apparel, found on the arrested person.

Finally, the arrested person must be taken to the police station. This is provided for in Section 9 of Act 30which reads:

A person who is arrested, whether with or without a warrant, shall be taken with reasonable dispatch to a police station, or other place for the reception of arrested persons, and shall without delay be informed in a language which the person arrested understands and in detail of the nature of the charge that initiated the arrest.

Types of Arrest:

- Arrest with warrant.

- Arrest without warrant.

These are now discussed.

Arrest with Warrant:

A. Meaning of a Warrant:

In the Black’s Law Dictionary, 9 th ed., a warrant is defined as:

A writ directing or authorizing someone to do an act, esp. one directing a law enforcer to make an arrest, a search, or a seizure.

The warrant is address to a particular person and to other officers of the court commanding him to apprehend a person suspected of a stated offence and produce him before the court.

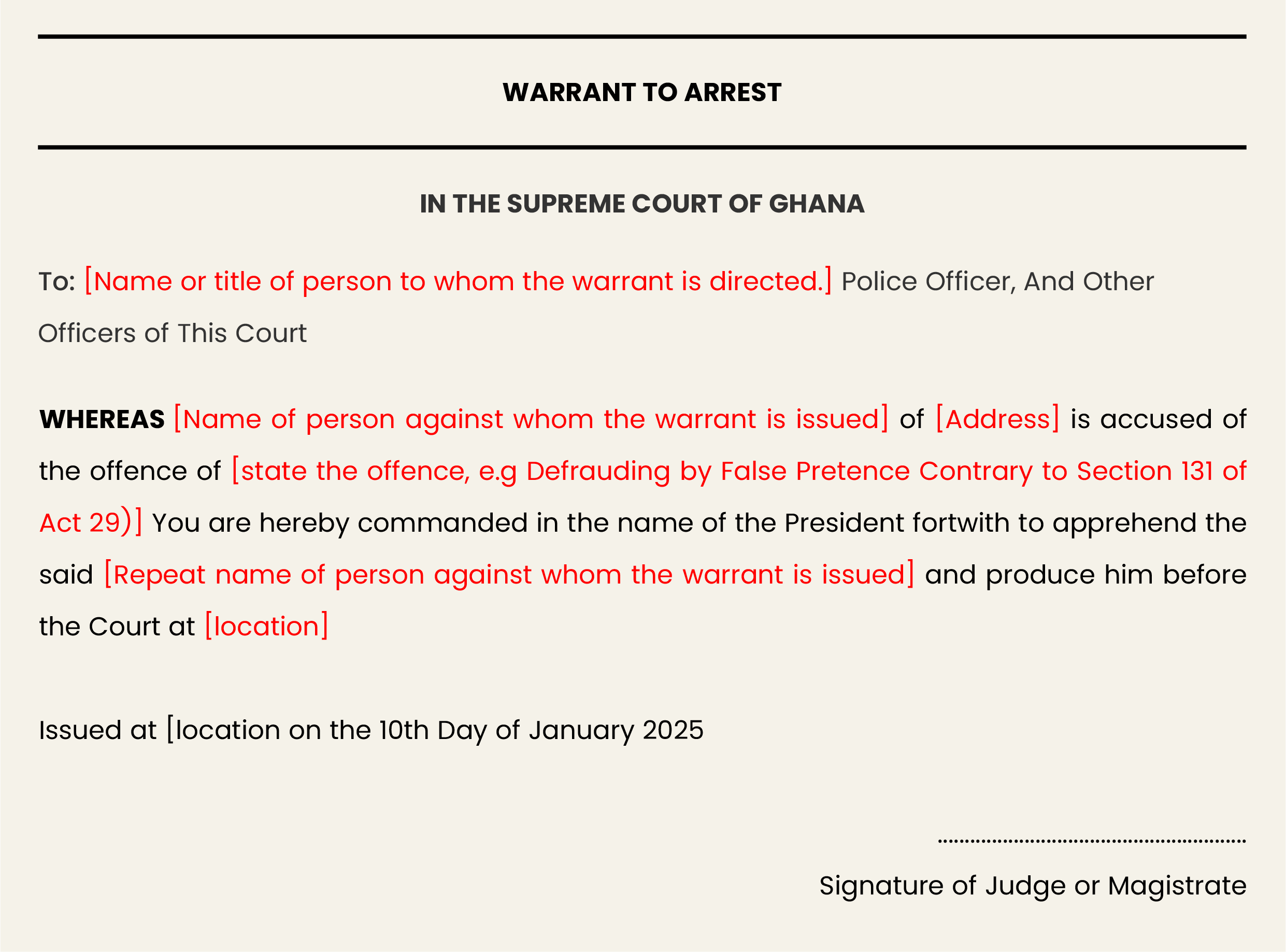

Below is a sample warrant:

The content of a warrant of arrest is provided for in Section 73 of Act 30.

B. What the Police Can Do with An Arrest Warrant:

First, the warrant expressly gives the police the power to arrest the person named on the warrant and suspected to have committed an offence.

Second, Section 4 of Act 30 gives a person acting under a warrant the power to enter a place and effect an arrest. In entering the place, the person acting under the warrant may enter upon admission by the occupants of the place or forcibly enter if such admission is not obtained or is denied.

Finally, in effecting the arrest, the police are generally required to notify the person to be arrested of the content of the warrant . He may also show the warrant to the person arrested if so required.

2. Arrest without Warrant:

A. The Common Law Position:

Under the common law, there can be an arrest without a warrant. This was recognised by the House of Lords in the case of Christie v. Leachinsky [1947] A.C. 573, H.L. In that case, Lord Viscount Simon gave the following exposition of what must be done following an arrest:

(1) If a policeman arrests without warrant upon reasonable suspicion of felony, or of other crime of a sort which does not require a warrant, he must in ordinary circumstances inform the person arrested of the true ground of arrest. He is not entitled to keep the reason to himself or to give a reason which is not the true reason. In other words a citizen is entitled to know on what charge or on suspicion of what crime he is seized.

(2) If the citizen is not so informed but is nevertheless seized, the policeman, apart from certain exceptions, is liable for false imprisonment.

(3) The requirement that the person arrested should be informed of the reason why he is seized naturally does not exist if the circumstances are such that he must know the general nature of the alleged offence for which he is detained.

(4) The requirement that he should be so informed does not mean that technical or precise language need be used. The matter is a matter of substance, and turns on the elementary proposition that in this country a person is, prima facie, entitled to his freedom if he knows in substance the reason why it is claimed that this restraint should be imposed.

(5) The person arrested cannot complain that he has not been supplied with the above information as and when he should be, if he himself produces the situation which makes it practically impossible to inform him, e.g. by immediate counter-attack or by running away. There may well be other exceptions to the general rule in addition to those I have indicated, and the above propositions are not intended to constitute a formal or complete code, but to indicate the general principles of our law on a very important matter. These principles equally apply to a private person who arrests on suspicion.

B. The Position Under Act 30:

The common law position has been said to have been codified under Act 30. In Section 10 of Act 30, it is provided that a police officer may arrest a person without a warrant if the person:

1. Commits an offence in the presence of the police officer.

2. Obstructs a police officer in the execution of that police officer’s duty.

3. Has escaped or attempts to escape from lawful custody.

4. Possesses an implement adapted or intended for use to unlawfully enter a building, and does not give a reasonable excuse for the possession of the implement.

5. Possesses a thing which may reasonably be suspected to be stolen property.

Beyond these grounds, subsection 2 provides that a police officer may also arrest without a warrant if he reasonably suspects:

1. That the person has committed an offence.

2. That the person is about to commit an offence.

3. That the person is the person for whom a warrant of arrest has been issued by the court. Here, the police suspect that the person he is arresting is the same as the person against whom an arrest warrant has been issued.

4. That the person has deserted from the Armed Forces.

5. That the person is a fugitive.

Note that an arrest without a warrant under the above circumstances can only be made upon a reasonable suspicion, characterised as the sort of common-sense conclusion about human behaviour upon which practical people are entitled to rely.

Also, while the police have the power to arrest without a warrant, the police must inform the person of the arrest, else an arrest may be described as unlawful. In the case of Amadjei and Others v. Opoku Ware [1963] 1 GLR 150 , the Supreme Court said:

A person who is arrested without a warrant is entitled to know as soon as is reasonably practicable that he is being arrested and also the grounds for his arrest. If the officer arresting fails to inform the suspect accordingly the arrest would be unlawful, unless the arrested man is caught red-handed and the crime is patent to high heaven.

Also, see the case of Asante v. The Republic [1972] 2 GLR 177-197.

Speed

1x