Note on Drafting a Charge Sheet by Legum

Drafting a Charge Sheet

Introduction:

This note will discuss the meaning of a charge sheet, its statutory recognition as a means of instituting criminal proceedings, its contents, the rules governing the drafting of charge sheets, and a model charge sheet.

The Charge Sheet:

Black’s Law Dictionary, 9th ed., defined this as:

A police record showing the name of each person brought into custody, the nature of the accusations, and the identity of the accusers.

In the Course Manual on Criminal Procedure, it is defined as:

A police record showing the name of each person brought into custody, the nature of the accusations, and the identity of the accusers.

Charge Sheet as a Statutorily Recognised Method of Instituting Criminal Proceedings:

In Section 60 of the Criminal and Other Offences (Procedure) Act, 1960, Act 30 , it is provided that:

(1) Criminal proceedings may be instituted before a District Court in either of the following ways—

(b) by bringing a person arrested without a warrant before the court upon a charge contained in a charge sheet specifying the name and occupation of the person charged, the charge against him, and the time when and the place where the offence is alleged to have been committed. The charge sheet shall be signed by the police officer or public prosecutor in charge of the case.

This provision, beyond specifying a charge sheet as one of the methods of instituting criminal proceedings, highlights some content of each charge contained in a charge sheet, such as:

i. Name of the accused.

ii. Occupation of the accused.

iii. The charges against him [the offences he is suspected to have committed]

iv. Time of the commission of the alleged offence

v. Place of the commission of the alleged offence.

vi. Signature of the police or public prosecutor in charge of the case.

If there are defects in the charge sheet, Subsection 2 provides that the validity of the proceedings instituted shall not be affected by such defects. Section 176(1), however, allows the court to make an order for the alteration of a defective charge sheet by the alteration of the charges contained therein. For examination purposes, however, it is essential to draft a charge sheet without defects.

Rules Regarding the Drafting of Charge Sheets:

The drafting of charges is governed by the following constitutional and statutory rules.

1. The Accused Must be Charged With A Specific Crime(s) That Is Defined and the Penalty Prescribed:

In Article 19(11) of the 1992 Constitution, it is provided that:

No person shall be convicted of a criminal offence unless the offence is defined and the penalty for it is prescribed in a written law.

In light of this, if there is only a prescription of a penalty without a definition of an offence in a written law, the courts will hold that the enactment prescribing the punishment is inconsistent with Article 19(11). See the case of Kpebu (No. 1) v. Attorney-General Civil Appeal No. J1/7/2015 .

2. The Act of the Accused Constitutes an Offence at the Time it Took Place:

In Article 19(5) of the 1992 Constitution, it is provided that:

A person shall not be charged with or held to be guilty of a criminal offence which is founded on an act or omission that did not at the time it took place constitute an offence.

3. The Charge Must be Drafted to Give Reasonable Information to the Accused:

In Section 112(1) of Act 30, it is provided that:

(1) Subject to the special rules as to indictments hereinafter mentioned, every charge, complaint, summons, warrant, or other document laid, issued or made for the purpose of or in connection with any proceedings before any Court for an offence shall be sufficient if it contains a statement of the offence with which the accused person is charged together with such particulars as may be necessary for giving reasonable information as to the nature of the charge and notwithstanding any rule of law to the contrary it shall not be necessary for it to contain any further particulars than the said particulars.

This provision reveals that a charge sheet should contain:

i. A statement of the offence with which the accused is charged.

ii. Such particulars as may be necessary to give reasonable information as to the nature of the offence. This is called “Particulars of Offence”

These are now briefly discussed.

i. Statement of Offence:

Under the statement of offence, you specifically mention the name of the offence and the enactment creating the offence. For example, if a person intentionally kills another person, the offence is murder. The enactment creating this offence is Section 46 of Act 29. Here is a sample:

MURDER: CONTRARY TO SECTION 46 OF THE CRIMINAL OFFENCES ACT, 1960 (ACT 29).

Notice how short and concise this is. What is also essential to note is that you must be extremely familiar with several offences under Act 29 to be able to draft this section of the charge.

ii. Particulars of Offence:

This section is drafted from the facts of the case and the elements of the offence as contained in the definition section of the offence.

In using the facts, you use the following (as highlighted in Section 60(supra)):

1. Name of the accused. Always write the name(s) of the accused in uppercase.

2. His occupation.

3. Date of the offence.

4. Place the offence was committed. E.g. Achimota, Nima, Newtown. Sometimes, you will see phrases like “in or around Dome.” This is just out of the abundance of caution if the prosecution is not so sure of the exact place the offence was committed.

5. Region of the offence. E.g. Greater Accra Region.

In using the elements of the offence, you use words and phrases contained in the definition section of the offence. For example, the definition section for murder, under Section 47, is:

A person who intentionally causes the death of another person by an unlawful harm commits murder, unless the murder is reduced to manslaughter by reason of an extreme provocation, or any other matter of partial excuse, as is mentioned in section 52.

The particulars of offence for a person charged with murder will read:

KOFI APPIAH, Software Developer: On 15 th March, 2025 at Kumasi in the Asanti Region and within the jurisdiction of this court, intentionally caused the death of one KOFI ABOTSI by an unlawful harm.

Notice the use of the phrases “intentionally cause the death” and “unlawful harm” above. These are contained in the definition of the offence of murder under Section 47 (supra).

4. Drafting Multiple Charges:

Sometimes, an accused may be alleged to have committed more than one offence. These multiple offences are often drafted in the same charge sheet but as different charges or counts. This is provided in Section 109 of Act 30 as follows:

For every distinct offence of which any person is accused there shall, subject to subsection (2), be a separate charge or count.

(2) Charges or counts for any offences may be joined in the same complaint, charge sheet, or indictment and tried at the same time if such charges or counts are founded on the same facts, or form or are a part of a series of offences of the same or a similar character.

For example, if a person, say Yaw Manu, agrees to act together with some other person to steal and later steals, he will be charged with the distinct offences of conspiracy to steal and stealing. Thus, there will be a distinct charge for conspiracy to steal and another distinct charge for stealing.

Note that if there are multiple charges, we separate them by heading and numbering each count. So with our example above, the conspiracy charge will be count one and will have a statement of offence and particulars of offence, and the stealing charge will be count two with its own statement of offence and particulars of offence.

5. Joinder of Accused Persons:

In drafting a charge sheet, offences committed by multiple persons may be included in the same charge sheet. Section 10 of Act 30 makes provision for this as follows:

(1) The following persons may be charged and tried together namely—

(a) persons accused of the same offence committed in course of the same transaction;

(b) persons accused of an offence and persons accused of abetment, or of an attempt to commit such offence;

(c) persons accused of different offences provided that all the offences are founded on the same facts, or form or are part of a series of offences of the same or a similar character;

(d) persons accused of different offences committed in the course of the same transaction.

(2) No trial shall be invalidated by reason only that two or more persons have wrongly been tried together on one complaint, charge sheet or indictment unless objection is made by any of the accused at the time or before he was called upon to plead.

Note that when joining multiple accused persons under the same charge, such as a charge of conspiracy, you are required to number all the accused persons. If it is one accused person, you do not number; just mention the name.

6. The Rule Against Double Jeopardy:

In Article 19(7) of the 1992 Constitution, it is provided that:

No person who shows that he has been tried by a competent court for a criminal offence and either convicted or acquitted, shall again be tried for that offence or for any other criminal offence of which he could have been convicted at the trial for the offence, except on the order of a superior court in the course of appeal or review proceedings relating to the conviction or acquittal.

If the same act constitutes the same offence under two different enactments, you must choose one of the enactments to charge the person. However, if the same act constitutes different offences under two different enactments, you will charge the person under both enactments.

In the case of Essien v. The State [1965] GLR 44-46 , the appellant was driving dangerously and on the same charge sheet, he was charged with one count of dangerous driving contrary to Section 18 of the Road Traffic Ordinance, 1952, and two counts of negligently causing harm contrary to section 72 of the Criminal Offences Act, 1960 (Act 29). He was convicted on all counts. He appealed against his conviction, arguing that the charges sinned against Section 9(1) of Act 29 which provides:

Where an act constitutes an offence under two or more enactments the offender shall be liable to be prosecuted and punished under either or any of those enactments but shall not be liable to be punished twice for the same offence.

In dismissing this argument, the court held that the singular act of driving dangerously resulted in two different offences, and he can be punished under both the Road Traffic Ordinance and the Criminal Offences Act, which are two enactments that define these two offences. The court relied on the decision of R. v. Thomas [1950] 1 K.B. 26 where it was advanced that:

The principle which was borne in mind and which must be remembered in this case is this, that it is not the law that a person shall not be punished twice for the same act. The law is that a person shall not be punished twice for the same offence. Bearing this in mind I would interpret section 9 (1) of Act 29 as stating that where one act or omission constitutes one offence under two or more enactments then the prosecution must charge and prosecute only under one of the enactments. Here the one act constituted two offences-not one- under different enactments, it was one offence under the Road Traffic Ordinance and another offence under the Criminal Code. Thus possessing firearms without authority is an offence under the Criminal Code and that same offence is known under the Arms and Ammunition Act, 1962.5 In this case the prosecution must elect under which enactment it will proceed.

In the case of Ababio v. The Republic [1972] 1 GLR 347-354 , the appellant was destooled for failing to attend meetings of the traditional council without a reasonable excuse. He was subsequently convicted under Section 5A (1) of the Chieftaincy (Amendment) Decree, 1966 (N.L.C.D. 112), that made such failure an offence. He argued that his conviction violates the doctrine of double jeopardy because he has already been customarily punished (destooled) for the act of failing to attend the meeting. The court, in dismissing this contention, said:

The common law rule that a man should not be put in peril twice as laid down in 2 Hawk. Pleas of the Crown, s. 36 can only be sustained where a plea of autrefois convict or autrefois acquit will avail. And it can be so sustained if the defendant has previously been in peril on a charge for the same or practically the same offence.

… It is not enough to show that the evidence which will be offered on the second charge is the same as that offered to prove the first… The principle is given statutory recognition in our Criminal Code, 1960 (Act 29), s. 9 which provides:

"9. (1) Where an act constitutes an offence under two or more enactments the offender shall be liable to be prosecuted and punished under either or any of those enactments but shall not be liable to be punished twice for the same offence.

(2) This section shall not affect a right conferred by an enactment on any person to take disciplinary measures against the offender in respect of the act constituting the offence."

The same act therefore can legitimately be a basis for two offences, and as it was pointed out in R. v. Thomas [1950] 1 K.B. 26 at p. 3 1, C.C.A. "It is not the law that a person shall not be liable to be punished twice for the same act." So in the case of the appellant even if the right to destool him were conferred by an enactment it cannot be a ground for the contention that as he could be punished customarily by destoolment as a chief, paragraphs 5A (1) and 5A (2)(b) were not intended for him as a person generally.

Summarily, his act of failing to attend meetings of the Traditional Council could be a customary offence and at the same time an offence under N.L.C.D 112. His punishment under customary law does not therefore prevent him from being punished under the Act. Besides, it cannot be said that the body that destooled him is a court of competent jurisdiction. See Republic v. Jinadu, 1948 12 WACA 368.

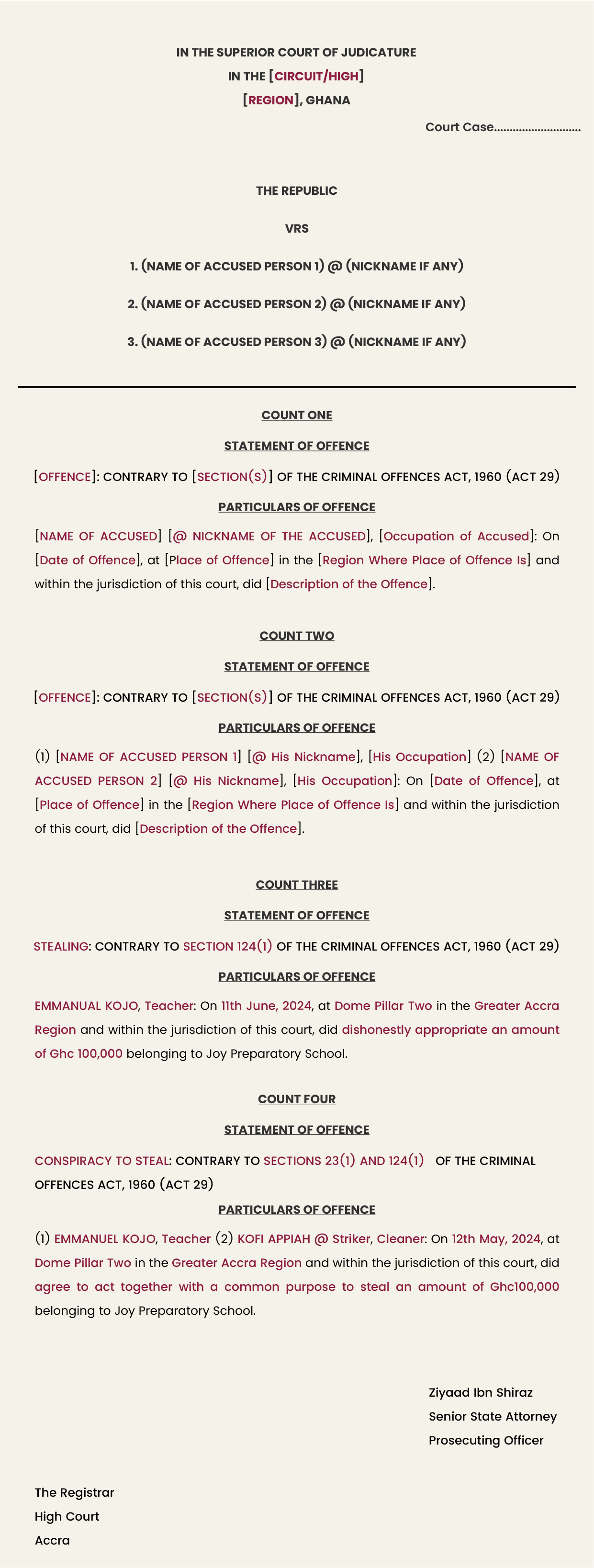

Model Charge Sheet: