Note on Types of Bail: Bail Pending Trial by Legum

Types of Bail: Bail Pending Trial

Introduction

This note will discuss the meaning of bail pending trial, the factors considered in granting bail pending trial and those that are not considered, the duty of the courts to grant bail pending trial if there is an unreasonable delay, factors considered in determining the conditions of the bail, and how to apply for bail pending trial.

Meaning of Bail Pending Trial:

This refers to the release of an accused person on bail while awaiting trial for an offence. It is granted by the court before or in the course of trial.

This form of bail is provided for in Section 96 as follows:

(1) Subject to the provisions of this section, a court may grant bail to any person who appears or is brought before it on any process or after being arrested without warrant, and who—

(a) is prepared at any time or at any stage of the proceedings or after conviction pending an appeal to give bail, and

…

In the case of Okoe v. The Republic [1976] 1 GLR 80-99 , the court, in commenting on this provision, stated that it “gives a discretion to any court to admit to bail any person who appears or is brought before it and who is prepared to give bail and to enter into recognisance with or without sureties as is directed by the court” and that the section “merely restated the power of the courts to grant bail to persons brought before them.”

In Boateng and Another v. The Republic [1976] 2 GLR 444-450 , the Court, in dismissing a contention that Section 96(2) of Act 30 empowers the High Court or the Circuit Court to grant bail at first instance, said:

This leaves section 96 (1) of Act 30 as the enactment which empowers applications for bail at trial at first instance before any court be it the High Court, circuit or district court.

Factors Considered by the Court in Granting Bail:

Although the grant of bail is discretionary, the court is guided by rules in exercising the discretion. The discretion is thus a bounded discretion. In exercising this discretion, the court is guided by provisions in Section 96(5) but does not have the power to withhold or withdraw bail merely as a punishment, as stated in Section 96(4).

The factors to be considered are provided in Section 96(5) and are as follows:

1. Whether the accused will appear to stand trial:

In Section 96(5)(a), it is provided that:

A court shall refuse to grant bail if it is satisfied that the defendant—

(a) may not appear to stand trial;

This condition has been severally held to be the main consideration for the grant of bail, as stated by Charles Crabbe JSC in Republic v. Registrar of High Court; Ex Parte Attorney-General (supra) . Similarly, in the case of Kpebu (No. 2) v. Attorney General No. J1/13/2015 , the Supreme Court advanced that:

if a court is satisfied from the facts presented in any case, that the accused when released on bail will not appear in court, then the court would be perfectly justified in refusing to grant bail by giving reasons.

Also, see the case of Seidu and Others v. The Republic [1978] GLR 65-72, where the court upheld the same principle.

When can it be said that the accused may not appear to stand trial? This is provided in Section 96(6), which reads:

(6) In considering whether it is likely that the defendant may not appear to stand trial the court shall take into account the following considerations—

(a) the nature of the accusation;

(b) the nature of the evidence in support of the accusation;

(c) the severity of the punishment which conviction will entail;

(d) whether the defendant, having been released on bail on any previous occasion, has wilfully failed to comply with the conditions of any recognizance entered into by him on that occasion;

(e) whether or not the defendant has a fixed place of abode in Ghana, and is gainfully employed;

(f) whether the sureties are independent, of good character and of sufficient means.

For instance, if the accused is likely to be punished for life if he is found guilty, and it appears there is overwhelming evidence to prove the guilt of the accused beyond reasonable doubt, the court may conclude that the accused is not likely to appear to stand trial and may consequently refuse bail.

2. Whether the Accused Will Interfere with Witnesses or Hamper Investigations:

In Section 96(5)(b), it is provided that:

A court shall refuse to grant bail if it is satisfied that the defendant—

may interfere with any witness or evidence, or in any way hamper police investigations;

3. Whether the Accused Will Commit any Further Offence when on Bail:

This is provided for in Section 96(5)(c).

4. The Nature of the Charge:

In Section 96(5)(d), it is provided that:

A court shall refuse to grant bail if it is satisfied that the defendant—

(d) is charged with an offence punishable by imprisonment exceeding six months which is alleged to have been committed while he was on bail.

(2) Notwithstanding anything in subsection (1) of this section or in section 15, but subject to the following provisions of this section, the High Court or a Circuit Court may in any case direct that any person be admitted to bail or that the bail required by a District Court or police officer be reduced .

Per the case of Seidu and Others v. The Republic (supra) , it can be said that the charge the charge must be supported with evidence.

5. Whether the Accused will be Safe When Granted Bail:

Beyond Section 96, in Kpebu (No. 2) v. Attorney General (supra) , the Supreme Court stated that:

It is worth stressing again that since the purpose of granting bail is to secure the presence of a person to attend his trial, and not based on his guilt or innocence, then where it can be demonstrated that the person is a flight risk or a danger to the community, or for his own protection (from vigilantes and mob attack)…

6. Whether there has been Unreasonable Delay in Prosecuting the Case:

An overriding consideration in determining whether an accused should be granted bail is whether there has been unreasonable delay in prosecuting the case. In the case of Okoe v. The Republic (supra) , the court, after examining all the provisions in Section 96 , advanced that if a trial unreasonably delayed, the accused has a constitutional right to be granted bail. The court advanced as follows:

Section 96 of Act 30 as amended by N.R.C.D. 309 consolidates substantially, the common law principles governing the grant of bail when a person is brought to court and when there is no question of delay in his prosecution. Once there is an unreasonable delay in prosecuting the case then section 96 of Act 30 is in my view inapplicable and Article 15(3)(b) and (4) of the Constitution, 1969, becomes applicable and in such a situation, bail in all cases must be given subject only to the conditions prescribed in the articles.

Article 15(3)(b) and (4) of the 1969 constitution is similar to Article 14(3)(b) and (4) of the 1992 Constitution .

Similarly, in the case of Okyere v Republic 1972 1 GLR 99:

It is clear that in Ghana the constitutional provisions draw a sharp distinction between bail for persons accused of crime and bail for person convicted of crime. Once it is established that a trial is not probable within a reasonable time, bail for persons accused of crime is mandatory. Failure or refusal to grant bail under such circumstances is a direct infringement of the constitutional rights of the individual, and may result in the quashing of any conviction and either an acquittal or an order for a new trial. In the words of Rutter J. in United States v. Motlow 10F (2d) 657 (7 Cir. 1926) at p. 662. "Abhorrence, however great, of persistent and menacing crime will not excuse transgression in the courts of the legal rights of the worst offenders. The granting or withholding of bail is not a matter of mere grace or favour." Once a trial is not probable within a reasonable time, the Constitution decrees no discretion in the judge in matters of bail. The law regarding bail for persons accused of crime has therefore undergone a sea-change since the Constitution and the old principles are no longer wholly valid.

A similar principle was upheld by the Supreme Court in Gorman v. The Republic [2003–2004] 2 SCGLR 784 , where their lordships stated that there is a duty of the court to grant bail when the accused is not tried within a reasonable time. In that case, the court, however, held that the presumption of grant of bail under Article 14(4) is rebutted in cases where a statute specifically disallows bail based on the nature of the offence, such as the situations outlined in s.96(7) of the Criminal Procedure Code. It may now be conclusively said that this decision has been modified in light of the declaration that section 96(7) of Act 30 is unconstitutional in the case of Kpebu (No. 2) v. Attorney General (supra) .

Factors to Not Consider in Granting Bail:

Two factors may be discussed here.

First, in Section 96(4), it is provided that:

A court shall not withhold or withdraw bail merely as a punishment.

This provision was applied in granting bail to the applicant in the case of Okoe v. The Republic (supra). In that case, a bail application by the applicant was denied, and he appealed, arguing that the trial judge refused bail as punishment because he did not like the way he is alleged to have behaved. The application was opposed by the Republic on grounds that the applicant is likely to commit further acts of forcible entry, that there have been many violent acts in the country and there must be an end to them, and that the alleged acts of the applicant show that he had not been sympathetic to his fellow men and had taken the law into his own hands. The court noted that per the case of R. v. Rose [1895-1899] All E.R. Rep. 350 , Lord Russell advanced that:

It cannot be too strongly impressed on the magistracy of the country that bail is not to be withheld as a punishment, but that the requirements as to bail are merely to secure the attendance of the prisoner at the trial.

Upon reviewing the grounds upon which the Republic opposed the applicant’s application, the court was satisfied that “all the grounds clearly advocate the use of the bail power as a punitive measure. This is clearly against the provisions of Section 96 (4) of Act 30, and for that reason, they must all fail.” It consequently granted the bail.

A second factor to not consider is whether the offence forms part of the offences mentioned in Section 96(7) of Act 30, which provided that:

A court shall refuse to grant bail—

(a) in a case of treason, subversion, murder, robbery, hijacking, piracy, rape and defilement or escape from lawful custody; or [As amended by the Criminal Procedure Code (Amendment) Act, 2002 (Act 633), s. (7)].

(b) where a person is being held for extradition to a foreign country.

In light of this provision, the court refused to grant bail to the applicant who was charged with murder and abetment of murder in the case of Dogbe and Others v. The Republic [1976] 2 GLR 82.

However, in the case of Kpebu (No. 2) v. Attorney General (supra) , the Supreme Court of Ghana stated that in light of Article 19(2)(c), which has a presumption of innocence, Section 96(7) of Act 30 is unconstitutional because it takes away the discretion of the court to consider a person for bail. The court delivered itself as follows:

The presumption of innocence embodies freedom from arbitrary detention and also serves as a safeguard against punishment before conviction. It also acts as a preventive measure against the State from successfully employing its vast resources to cause greater damage to a person who has not been convicted than he can inflict on the community. Therefore, in my humble view any legislation, outside the Constitution, that takes away or purports to take away, either expressly or by necessary implication, the right of an accused to be considered for bail would have pre-judged or presumed him guilty even before the court has said so. That would be clearly contrary to this constitutional provision which guarantees his innocence until otherwise declared by a court of competent jurisdiction.

Factors Considered in Determining the Conditions of the Bail:

In determining the conditions of the bail, Section 96(3) provides that:

The amount and conditions of bail shall be fixed with due regard to the circumstances of the case and shall not be excessive or harsh.

How to Apply for Bail Pending Trial:

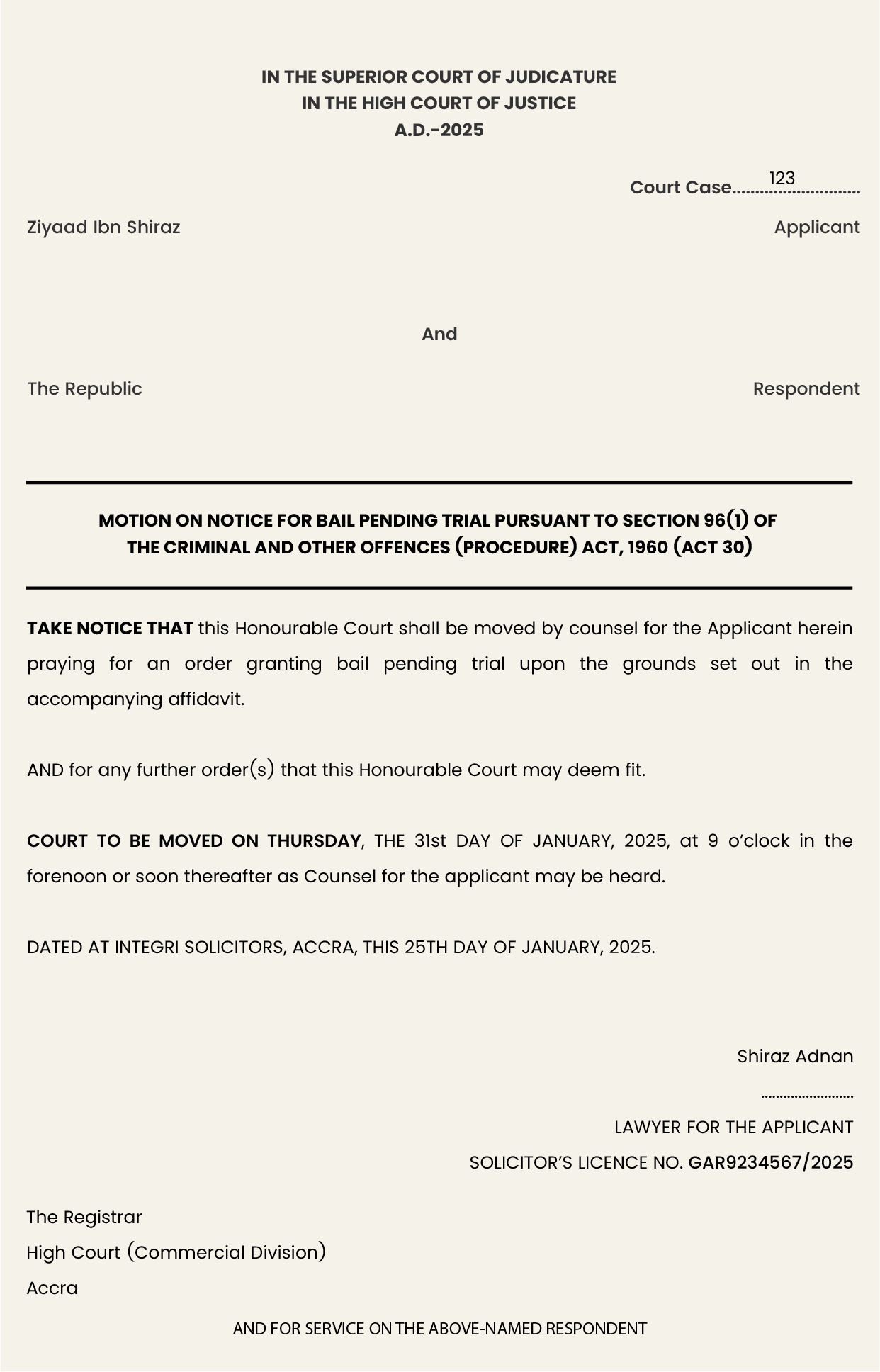

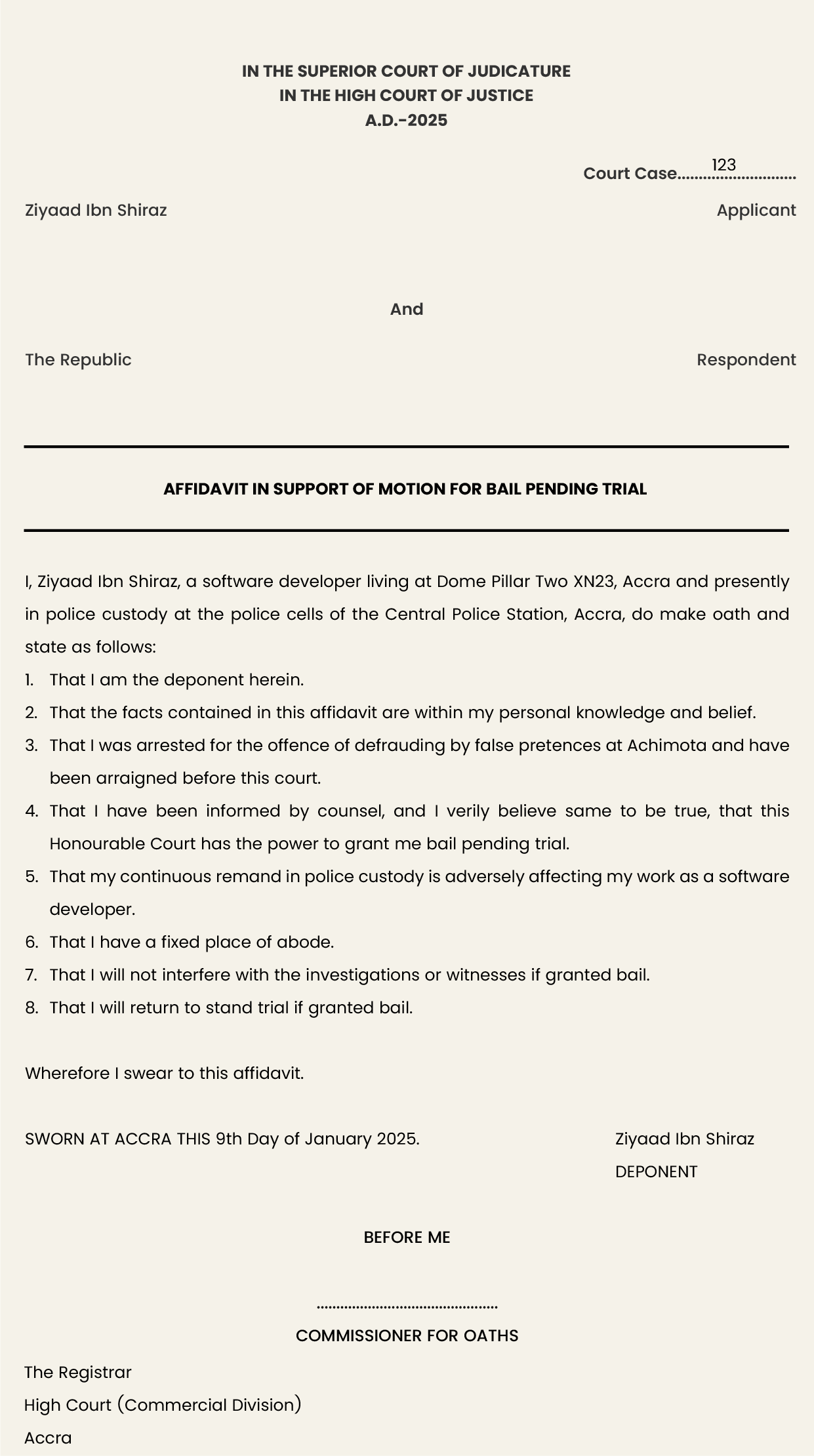

Bail pending trial may be applied for orally or in writing. If the application is in writing, it is done by a motion on notice supported by an affidavit that shall state the following (some of which are for the purpose of making it more likely that the court will grant the application):

i. The offence for which the applicant was arrested.

ii. A statement that he shall appear to stand trial. Or

iii. A statement that he shall not interfere with witnesses or evidence or hamper police investigation. Or

iv. A statement that he shall not commit further offence when on bail.

v. That he has people who are willing to stand as surety.

Below is a sample of the motion for bail pending trial:

Below is a sample of the affidavit in support of the motion:

Speed

1x